When I left for my semester abroad, I was full of anticipation to spend five full months in the exciting city of Istanbul. A mere three months later – after having struggled with sexist police officers, stone-hearted doctors, indifferent university officials, after battling the language barrier in a million confusing phone calls, after tantrums, crying fits and endless hours of conversation deep inside someone elses’s spiritual abyss, after all this incredible madness – I left the country as a desperate mess, looking forward to nothing more than hiding from the world under a blanky at my parents house. A recapitulation of What the fuck.

It’s been two years and I haven’t heard back from the girl whose story this actually is – let’s call her… Mira. I know Mira wouldn’t want me to tell you too much of her story, so I won’t. I will only tell you as much of hers as you need to know to understand mine.

Every time I think back to that time in November, I always end up going over the same moment when a few words made me realize how much of a mess we were all in.

It was late evening on a Sunday that had been a rainy and cold one, and I was on the phone with Gamze. She was the Dean of the faculty we studied at, but more importantly, she was also the coordinator of the exchange program we were in. I had just recounted her what Mira had told me – about her new roommate, the dinner, the drinks at his friend’s place, the music, the fun. The blankness. The pain.

There was a short silence before Gamze returned anything to my breathless report – a silence I still somehow wish she’d never bothered to break at all –, then I heard her voice ringing in my ears: “Why did she do this? She should not have done this”. It wasn’t a real question of hers, she didn’t expect me to answer. And I didn’t expect her to help. Not after hearing that.

Merhaba / Hello

We had met Mira at university, where she, too, was an exchange student. We, that’s my friend Julia and I. When we first met Mira, we didn’t like her very much.

The three of us were the only* exchange students at a university where nobody really seemed to care about us. Most of our fellow students showed some interest when we first showed up, but that didn’t seem to last. All the invitations and plans never turned into anything real. I know it sounds terrible, but with most of the other students, we weren’t even able to communicate much. The little Turkish we had managed to learn didn’t really help with anything except small talk and to be honest – neither did their English. I am not trying to be ignorant or rude here, we did study at the Department of English Literature though, so make of that what you will.

(*There was actually another girl from Germany, but we never even saw her once.)

At one point in the beginning of the semester, the three of us were even asked to please not come back to a certain class because it would be real bummer for everyone if it had to be taught in English instead of Turkish just because of us (the class was about British Romanticism).

Benim adım Maria, öğrenciyim / My name is Maria, I am a student

So, to put it mildly, we were having a bit of a rough start at uni, but I don’t want to only complain. The language issue also made classes ridiculously easy to handle and therefor left us with an insane amount of free time to explore and – for my share – fall in love with Istanbul.

I was so busy strolling around, exploring new places, sipping my coffee and befriending every street cat I met along the way, that I didn’t even notice we were a little on our own, Julia and I. But after a while, it did get a bit lonely.

Bir chai istiyorum lütfen / I would like a tea please

I’m not saying it’s a nice reason – but this is pretty much how we started to hang out with Mira. Because she was there. I mean, she was also irritatingly full of herself and shockingly ignorant about the country we all lived in. The awkwardness of many situations still makes me cringe with shame today. Like when we were out to eat balık ekmek (fresh fish and some salad inside bread, literally the simplest and best food there is by the way). Julia and I would smilingly struggle to order our meals in Turkish and secretly beam with pride when it actually worked.

But Mira, although she knew enough Turkish, would just frown at the waiter and order tea in English without please and thank you. Or when she kept on telling us loudly about all the times she got “SO mad” when people on the street addressed her in Turkish, mistaking her for a local.

It wasn’t that she was always like that. She could be a real laugh sometimes and say smart-ass things in conversations. We were mostly happy to have her around despite her tendency to rant about this and that and Turkey in particular. The three of us went out a few times – we drank, danced and had a good time.

And that was exactly what we had been planning for the weekend, the one that ended with my phone call to the Dean. A friend of mine from Germany was unfortunate enough to visit in just those days and we wanted to go out. When we had invited Mira to join us, she’d agreed. Only that she never showed up.

We texted and called, but she wouldn’t answer. In the short time we knew her, Mira hadn’t exactly proven to be the reliable type. Saying she would show up and actually doing so were two things not necessarily connected – so we weren’t too worried at first.

Bir doktora ihtiyacım var / I need a doctor

A few minutes after I’d hung up on Gamze, the four of us sat crammed into a taxi: Mira, Julia, my poor visiting friend and me, clinging onto a piece of paper with the scribbled address of a hospital on it. I remember stepping into the place that night and thinking “Well, this isn’t bad”. Honestly, I’d been terrified to see a hospital from the inside, but this one looked alright to me. It wasn’t until a little later that night that I found out how trustable my gut feeling was.

In a matter of minutes we were talking to a very nice, very understanding and very English-speaking doctor. That is, I was talking for Mira who was sitting on the examination table, apathetically starring off, terribly pale and barely addressable. I remember hoping that she wouldn’t faint, then hoping I wouldn’t faint and almost laughing. I was very nervous, but also really confident we had made the right decision to bring Mira here.

But as per usual, it turned out I was wrong. In a tone that was probably supposed to sound consoling, the doctor explained to us that the hospital – because of course, this was a private one – was not allowed to do anything for us. Apparently, when there is a police investigation at hand (like there was here), private hospitals cannot get involved because the results of their examinations are not accepted as evidence in such cases. Only public ones can provide such evidence. With a little shrug and an apologetic look on his face, the nice doctor led us back to the entrance and before we really knew what was happening, we were on the next taxi, on our way to the closest public hospital.

İngilizce biliyor musunuz? / Do you speak English?

You might be wondering whether it was really a good idea for four foreign girls in their twenties to just walk into a public hospital in Istanbul, in the middle of the night, without any significant language skills to explain our problem. Shouldn’t we at least be accompanied by someone to support us verbally – a Turkish possibly? Well yes, I agree, we should have.

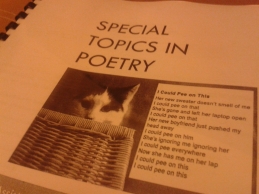

But as I had understood earlier on the phone with Gamze (when she was done blaming Mira for what had happened), she would not be able to come along because of a conference she was leaving town for the next day. As she explained wordily, neither could her husband (who was a professor at our university, too), because as soon as he had understood what we were discussing on the phone, he had pretty much lost it and was yelling in the background like a mental person. There were two other teachers whom I trusted enough (one being Şeref, the one with the cat poem, for obvious reasons) so I asked Gamze if she could contact them on our behalf, but she refused, arguing that they lived too far away to come over that same night.

[Just in case you were wondering: We did try and reach out to Mira’s country’s consolate. Their emergency contact was really nice and helpful, but spontaneously leaving his office to accompany us went beyond his capacities. He said he could only advise us to get Mira examined as soon as possible – but didn’t seem to know about that private / public hospital issue.]

As I said, it was Sunday then and the night of concern had been on Friday (Mira had spent 24 hours locked in her room before reaching out to us) – so we had absolutely no time to lose. Even now, the chances to still find some trace of whatever had made her pass out two days ago were small. If we didn’t want to lose that option altogether, we had to act immediately. And so, devoid of any support, we did.

The public hospital, I’m just gonna be blunt about it, matched many nightmares I have ever had. In the waiting room we entered, it was incredibly hot and it seemed like all air in there had been used up months ago. There were people everywhere, many of them sleeping in the most uncomfortable positions, stretched out across the brutally hard seat rows.

Çok az Türkçe biliyorum / I speak very little Turkish

I don’t remember what I said to the nurse at the reception, I only remember she waved at us to follow her to the emergency room that lay behind two doors at the end of the room. She wouldn’t let all four of us enter, so only Mira and I went ahead.

It was even hotter in here and the room was filled with all possible human odors and a thick repulsive smell of hospital food that made me want to vomit. Although the room was less crowded, it was buzzing with chaos. I wrenched myself away from staring at what looked like dried blood in one corner and – telling Mira to stay right behind me – I tossed myself right into the crowd of people who were trying to drown each others voices out and get one of the few doctors to listen.

“Do you speak English?”, I hopefully approached one of them in Turkish. He looked at me for a split second, then dismissively replied “You speak Turkish” and was about to turn away, but I yelled some words after him and he turned back around. Maybe he understood it more from looking at the ghost-like girl next to me than from my words, but he stayed with us. By then, it was around 11 pm. Our night wouldn’t be over until 8 in the morning.

In the weeks that followed, weeks that I spent almost entirely by Mira’s side, I never really talked to her about that night. We talked about every- and anything, but I never found out how much of that Sunday night Mira was really able to grasp. If I knew, maybe that would put my experience into perspective, but things being as they are, I can only say that what followed this little conversation with the doctor (that should definitely have been confidential but instead was shared with an audience of 30 something random people), was the worst night of my life (yet to be beaten).

İmdat / Help!

In a seemingly endless odyssey that I swear makes every fucking Kafka novel look like a birthday party all with a bouncing castle and shit, we were shoved from nurse to nurse, doctor to doctor, room to room. After Mira had finally been examined by a female doctor (who is forever on the list of people I want to punch in the face, for impatiently telling Mira to “just calm down” during a procedure that is not exactly nice even when you’re in a normal condition), we were suddenly asked to leave.

As one of the doctors explained, you were supposed to report your case to the police first, which we hadn’t known (surprise). So when we couldn’t show a certain paper, we were pretty much kicked out. My insistent concerns that they hadn’t even taken a blood sample from Mira and we couldn’t afford to lose more time, were brushed aside.

We’d have to press charges first, then come back, they told us, and there we were, out in the night again, waiting for cab number three to take us to the nearest police station. I tried not to think of what Gamze had said on the phone: That we should under no circumstances contact the police about this without a Turkish male to come along with us. “They will never take you serious”, she had said.

In her defense, after refusing to send her husband or Şeref over, she did offer to contact one of the students to come along with us. But it had been the one thing Mira had made me promise before she agreed for me to call Gamze – that none of the other students could know. Maybe I should have talked Mira out of that, maybe I should have insisted that Gamze help us somehow – but I didn’t. So there we were, walking into the police station like we knew anything.

Arkadaş / friend

As you can imagine (or I don’t know, can you?), things got worse in there. We did interrupt the officers’ smoking and smartphone games though, so I think we deserved some of the malice and mockery we received. We weren’t even asked to come inside one of their offices, we weren’t even offered TEA (which from what I learned about Turkish standards is like impossible), we just stood there on the corridor, freezing in the cold wind every time the door opened for one of the cops to go smoke. For what felt like the millionth time, I explained what had happened and asked them to please fill out the paper we needed to get Mira examined further.

One of the police men spoke very good English (in my memory he was also the nicest one, see any bias here?), and he translated the story to his colleagues who nodded and frowned, cracked some jokes we didn’t understand, some yawned loudly over the course of it and left for a cigarette, some started to play with their phones again.

Still standing in the hallway, the English man (I’m just gonna call him that) agreed to get the paperwork done and even come back to the hospital with us for translation. When I thought that was too good to be true, I was unfortunately right again. Because before he would come along with us, the police wanted Mira to take them to the address where she had been on Friday night. Note: It was the middle of the night, Mira was beside herself to a point where I don’t think she was even following the conversation and they asked her to show them the house where all that had been done to her. Seemed like I had to get used to not believing my own damn ears.

kız / girl

She didn’t want to and we didn’t want her to, but we didn’t see any way around it. I mean, the officers didn’t really give us a choice. We take them there, we get the fricking paper, they even accompany us to the hospital. It seemed like our best option, unfortunately.

So a few minutes later, Mira and I sat in the back of a police car speeding across the city in an unbelievable pace. (The other two hadn’t been allowed to come along and had to wait at the police station). With Mira’s clouded mind as our only guide, it took a while to find the place and the gentlemen in the front seats even had the nerve to get all impatient on her.

When we finally found the right house, it was my shrieking tantrum only that stopped them from making Mira, the traumatized human puddle of misery, actually GET OUT OF THE CAR and show them the doorbell. I mean, seriously? I think I’d acted like a reasonable grown-up so far, but to me, that was just asking too much of her. I kinda lost it there. I yelled and I insisted she stayed in the car. She pointed out of the window to show them the right apartment, they looked around for a bit and we left. God damn it.

Back at the hospital (we did of course not go back to the police station to get the other two girls as we had discussed earlier) the kafkaesque journey continued. You could say things got a lot easier now that we had the English man for talking business and his colleague for grumpy looking business. It did also get more confusing though, because everything seemed to happen at a much faster pace and nobody bothered to explain anything to us.

Teşekkürler / Thank you

Every once in a while, when I had annoyed him enough, the English man would give me bits and pieces of information, like what doctor Mira was going to see next or what document we were waiting for. I wanted to know everything and to be frank, I didn’t trust them one little bit. At one point they directed us back to the police car and I immediately went to the edge of flipping again – until it turned out they were only driving us to another hospital building so we wouldn’t have to walk through the cold night.

So we spend a really long, really confusing night in what seems like every corridor this hospital had. When we went to see the psychologist (because apparently that’s what Mira needed, not sleep and peace, but another person who doubted her), I swear there was half an hour in which I considered whether or not I was inside of a horror movie. Not only was the building all dark expect for the room we waited in while Mira was talking to the ill-tempered psychologist whom we’d just woken up in the middle of the night. We could also hear the not so distant voices of people screaming throatily in their sleep and peek over the reception table to see them move around on the green tinted screens of the surveillance cameras. Even the police men next to me kept nervously looking over their shoulders and tapping their feet impatiently, like they couldn’t stand this place one bit more than me.

When we finally left the hospital with some papers and (on my part) very little understanding of what they were saying, I could see the sun rise over the nearby rooftops. I was exhausted but relieved. Finally we would be able to go home and get some sleep.

Hoş geldiniz / Welcome

“Home?”, asked the English man. “You can’t go home now. We have to go back to the police station, she hasn’t made her statement yet”. She, I remember being quite irritated that he wouldn’t just use her name, was standing next to me like the innocent sheep she was, completely aloof, like she was just a casual bystander to the drama that was her life.

I might have freaked out at that again, maybe they’d expected me to. And I should have. Mira had already taken too much that night. She should be allowed to go home and get some rest. But honestly, I was worn out to defenselessness. I asked please, may we go home and do this tomorrow? They said no – and off we went.

The other girls had long been brought home after some awkward hours spent with drinking tea and being asked strange questions about Mira, so we didn’t find any friedly faces back at the station. Instead, we were faced with a new officer. He was fatter than the rest of them and maybe that’s why it was his job to write the reports. The English man stayed around because his fat colleague did not know enough English to understand our statements properly. He did however know words to compliment us on our looks and persistently tell us what “beautiful girls” we were.

Problem yok / (There is) no problem

I had felt uncomfortable before, but now my nerves were so frayed I could hardly sit still on my chair next to Mira. I declined the offer for tea to be deliberately rude and because a small, but embarrassingly fierce voice in my head wondered whether it would be save to drink it. I admit, that’s a close to insane thing to think, but it seemed perfectly reasonable to me at that point.

The testimony was hard for Mira. She would look at me for help a lot of times when she couldn’t go on speaking, but the fat guy shushed me when I tried to add something. When she teared up at one point, fat guy nervously clicked his pen until she continued. English men and fat guy asked Mira all sorts of questions that – I have a feeling – would not be asked a woman in the same situation in, let’s say, Germany. Or maybe they even would, but once. Like: “Was your room mate your boyfriend?” or “Did you have sex with him?”, “Are you sure you didn’t?” and “But you did offer him sex, right?”. I wasn’t witnessing testimony, but an interrogation.

When Mira answered a specific question with “Yes” and “Four shots of wodka”, their eyebrows rose up in (fake) shock. Really, so the girl had gotten drunk with two guys and now she’s complaining? I knew this wasn’t going well. Mira apparently didn’t understand any of that – in fact, at this point she seemed to really wake up from her drowsiness. “Excuse me?!”, she ranted almost in her normal tone. “Where I’m from, we know our alcohol. I don’t get drunk from four shots of wodka”. (I do, by the way).

çok güzel / very nice

About an hour into the interview, Mira’s phone started to ring. She stared at the display for a moment, then silently held the phone out across the desk to the two men. It was her room mate calling. Fat guy told us to ignore the phone, but shortly after she received a message from the same number. It read “What did you do?”.

We were still talking to fat guy when half an hour later, he was the one to receive a phone call. “They have been arrested”, he said sternly. “They are being taken to a police station right now”.

I thought wow, that was fast and unexpected (they hadn’t told us anything about locking them up the same night), then I had a really sick thought. They wouldn’t bring them to this police station, would they?

“Of course to this police station, where else?”, said the fat man and Mira’s eyes almost popped out of her head, then an instance later he laughed as if he’d just cracked an insanely funny joke and apparently, he really thought he did. “I’m joking”, he said, shaking his head at the look of our shocked faces. I couldn’t even think of a response, just patted Mira on the back to stop her from shaking like a leaf.

So no, the two guys were not brought to the same police station we were in, lucky us. It was around 7.30 in the morning when the police were done asking Mira questions that allowed no other than the suggested answers. Fat guy printed out some papers in Turkish and had her sign them. I protested she sign anything we couldn’t read first and asked for a translation, they said no. I asked to take copies, have them translated elsewhere and come back tomorrow for the signature, they said no. She signed them anyway.

Yabancı / foreign(er)

Alright then, I thought, the least we can expect are copies of the documents to take them with us. Believe it or not, they said no. I hadn’t thought I’d be capable of any more fighting that night, but confronted with that outrageous injustice I got so angry I jumped up from my chair without even noticing (when I used to read that expression in books I always thought that was bullshit, but I get it now). Literally on the edge of tears from all the fury and disbelief, I went bonkers and insisted to get the copies done. Fat guy turned around to his coworkers to complain about me (I had been in Turkey long enough to sometimes understand when people obviously talked about me), but I didn’t care. I think that was the one moment in my entire life when I did not give a single damn about what anyone in the world thought about me. The only thing I cared about were these goddamn papers.

I did get them. Then a door slammed in the face. It was eight in the morning, we had been with the officers since midnight and I really think they could have offered us a ride home (I know they did for the other girls that night). I didn’t care. I didn’t care about anything. We crashed into the next cab, then into our apartment and into bed. In mine, there was Julia waiting for us to come home (we’d agreed to share my bed so Mira could have Julia’s for herself). She didn’t say a word when I lay down next to her, but I knew she was awake. “It was… so bad”, was all I managed to say before I burst into tears and she hugged me like the unconsolable child I was.

Günaydın / Good morning

Maybe you’re thinking that – although the events had been terrible as they were – everything would get better now. Mira would go home to her family and get the proper psychological help she needed and Julia and I, no matter how struck by the experience, would go back to the somewhat normal student life in Istanbul we’d lived before.

Althought that would have been the only logical consequence, none of these things happened. In fact, when this one Sunday night had been particularly confusing, scary, intimidating and what not – it was only now that things got real messy.

For reasons I am one hundert percent sure I will never understand, Mira’s mother didn’t allow for her daughter to come back home. Just to make sure that message really came across: Mira didn’t have the money to buy a plane ticket and her mother wouldn’t pay for one. Not knowing their language, I have no idea what they discussed in their endless phone call sessions and Mira wouldn’t got into detail about it, but the result was clear: She stayed.

Now what were we supposed to do with her? She was traumatized from the past events, she was now confronted with the disturbing fact that her mother seemed to not care for her at all and she had nobody to turn to in this city, except for us. That she would live with us now wasn’t even something we talked about, it was just the most natural thing to happen. We did have a spare room in our flat, but it wasn’t furnished, so we thought the couch would do as a temporary solution, but unnecessarily so: Mira was so scared to sleep by herself that I let her share my bed most of the time.

Anlamayorum / I don’t understand

Over the next couple of days, our house was like Grand Central Station, people came and went and came back again, we never really knew who was coming. A teacher and her police friend came by to translate the papers we’d received, but that didn’t really help anyone. Gamze showed up after two days, making a grand entrance and pouncing on us with her too loud and too long justifications of why she hadn’t been able to help, repeating over and over again how “inexperienced” the university was with such cases.

Hopefully at some point in my life I will forget how this woman pronounced this impertinence of a word with her smooth Turkish rrrr and her rumbling voice. We tried our best to ignore her unstoppable lecture, but it was hard to stand hearing this full grown, resolute professor who liked to go on and on about the foulness of patriarchy in each and every of her clases tell us how she had lacked experience to do the right thing in this situation, while we 20 something year old girls had simply decided to help.

As maybe you can imagine from my describtion so far, Gamze hasn’t been very helpful in any part of this story. A few days after, she suddenly called to tell me they were coming to pick us up and bring us to a hotel for our own safety. We realized that was probably only because we’d just informed our home university about the events and they had prompted Gamze to support us, but nontheless, it did unsettle us: Were we not safe in our home?

I for my part had never felt entirely comfortable in our ground floor apartment that seemed to groan and crackle a lot more when it was dark outside. So as soon as the safety issue had been pointed out to us, I lost my feeling of being sheltered altogehter. Maybe because we didn’t want to give Gamze the satisfaction that she had actually done something for us now that she was asked to, maybe because we thought it wasn’t a good idea to give up our private rooms where each of us could be in peace for one hotel room for the three of us, we declined the offer. Only when Julia left for a couple of days, Mira and I moved to the hotel for that period of time. I was so insecure I thought I couldn’t handle being home alone with Mira.

The consulate man, whom I had talked to before about the examination, became a regular to us. He turned out to be as nice and helpful as I’d thought and he managed for Mira to be examined and treated further in a local hospital. Lots and lots of official buildings and doctor’s appointments followed, and we accompanied Mira through all of them.

Nasılsın? / How are you?

The weeks started to pass and I spent more and more time with Mira. I still wasn’t sure whether to like her or not, only that now, I didn’t feel like I was allowed to make that decision anymore. I felt obliged to be there for her, and of course, that was somewhat true. And I was there for her. Like in that first Sunday night, I did everything that was to be done. I don’t think I did anything wrong when it came to Mira – but I messed it up for myself.

Because the more time passed, the less could I still separate myself from her. I didn’t set boundaries – or I didn’t think about doing that until it was too late. Julia was a lot smarter than I was. She took care of Mira, she made her laugh when she cried the hardest, she was amazing. But she was also strong enough to say: This is where I need to start taking care of myself before I go crazy here. So she’d take her time and space, get out of the house and see something else. She lived her life. I didn’t.

I couldn’t leave Mira alone, because I knew it was so much harder for her. Even when she started to act real weird on us – when Mira accused us of taking money from her for example – I didn’t manage to see her as anything else than a victim I had to protect. Even when she’d clearly started to play us off against each other, I didn’t feel capable of talking back to her. Once, when we were out to eat with some friends, she openly complained to them about Julia and me only speaking in German at home and deliberately excluding her. Julia got really mad at her for asserting that (especially because it wasn’t true) but I just couldn’t. I mean, I did get mad, but I could’t tell Mira “enough”. I just let her walk all over me. And today I even think Mira knew that very well. Of course, she was unstable, she was lost, she was helpless. But she also knew how to play me like a fiddle. No matter what she’d do, the only thing I was ever capable of thinking was “She’s younger than my sister” and I knew I couldn’t go on to do what was good for me – which would have been to get at least a very little distance from her.

Iyi yim / I’m fine

I knew I should have gotten away from Mira every now and then. Julia told me again and again and I knew very well that she was right, but I simply couldn’t. And that’s how I ruined it for myself.

Because if you’re like me, you’re bound to lose in a situation like that. In an apartment where you suddenly start hearing noises that aren’t there. With a consulate member telling you that the offenders’ families and friends are probably gonna somehow reach out to you: either to sweet talk you out of the charges, to offer you money – or to scare you. With phone calls coming in from unknown numbers. With the guys being set free after two days because Mira had been drinking. With our landlord offering to play some contacts with the local police so the offenders would “at least have their legs broken” if we can’t get them arrested. If you’re anything like me – and you can’t get any (emotional) space between yourself and all that – you’re going to go crazy. Like I did.

You know, I haven’t had the easiest time in Istanbul in the first place, but I had honestly been in love with the city before. The glittering bosphorus that looked so different every time of the day. The crowded streets buzzing with life. People’s smiles when you made an effort to say something in their language. The food, the smells, the sounds. The cats everywhere. The incompatible contrasts that jumped at you on every other corner, the mechanic sound of the muezzin’s call for prayer, the smell of roasted chestnuts, the ferrys, the seagulls, the markets, the neverending discoveries. I’d been head over heals for that – and now?

I admit, some weird things had happened to us before, we’d met some obstrusive guys who wouldn’t take a “I have a boyfriend” for an answer (let alone a “no”), but we’d mostly laughed about these things. Now, all I could see were reasons to be afraid. My appreciation for the city was almost gone and along with it my curiosity and drive to explore. The only thing left was my growing sense of danger. I couldn’t laugh about the too interested looks of men in the streets anymore. I couldn’t ignore them or maybe even pull a funny face at them and simply go on. I was scared although the odds of anything happening to me were as high as they’d been before and I knew that. But it didn’t help: I was scared out of my mind.

Almanım / I am German

You know, I’m not a little dumbass who thinks that these kind of things don’t happen in the world. But what messed with me on a very profound level was the fact that nobody gave a shit about what had happened to Mira. Yes, Julia and I had helped her as I thought anyone would – and to realize that wasn’t true has been hard on me. Especially the fact that the university we studied at denied us any help whatsoever left me feeling so helpless and unprotected. I knew if something bad happened to us, they wouldn’t care for my or Julia’s well-being more than they had for Mira’s. I couldn’t help but feel completely lost in a city of 18 million strangers.

There was only one possible way for me to maybe be able and go back to enjoying myself in this city and that was without Mira. I knew that with her by my side, I would never take care of myself for one second. But I didn’t know what to do about that. She couldn’t leave, her mother wouldn’t pay for her flight because of whatever. I couldn’t just leave her alone and “do my thing” because that just isn’t how I work. Maybe I should’ve just stormed into one of the conversations Mira had with her mother and yelled at her mum like I’d yelled at the police men to get the papers that I knew we should have. Maybe I should have just told her to stop being the most terrible human possibly imaginable and get her daughter out of there because she needed her family and her home. Looking at it now, that might have even worked. But of course, I didn’t do any of it.

görüşürüz / see you

Thinking about those weeks now, I have come across another realization and it’s probably the hardest one to accept. Maybe I didn’t even want Mira to leave. Maybe I wasn’t really as ready as I thought to go back to an ever so happy Erasmus-life. Maybe I was so wrapped around my pain and fear and misery that I somehow wanted to keep her there, as my permanent excuse to stay at home. Maybe I just couldn’t face reality just yet, maybe I needed someone elses misery to cling on to, to justify my own. Maybe I used her more than she used me.

So when the weeks passed and I grew more and more miserable, I started to think about going home and soon enough, it was pretty much the only thing I was thinking about: the safe harbour of home. For my semester abroad, I had to stay in Turkey for at least three months as to not get in trouble at uni, so that’s what I did. The flight I booked would take me back home exactly three months and two days after my promising arrival in Istanbul.

When I told Mira that I would leave, she looked really confused and she was clearly waiting for me to explain what that meant for her. That same night she talked to her mother on Skype. Us usual, I heard her voice from Julia’s bedroom where the wifi was strongest, but I didn’t understand a word. I don’t know how or why, but Mira’s mother agreed to have her fly out of Turkey the same day I left for Germany. (Seriously, she made that a condition, I’m not even commenting on that shit anymore.)

When my time in Istanbul was finally limited, I started to think about all the places I’d still wanted to go and see and I started to mourn my lost opportunities to do so. But I also felt like it was my own fault for giving up so soon. Because as soon as I knew Mira was going to leave, I felt like I could’ve stayed. But after all, I did look forward to my home and I still felt really shaken from what had happened. And honestly, I also felt like it was too late to change my mind. What if Mira’s mum would find out that I wasn’t leaving after all and would make her stay, too? I couldn’t do that to anyone – not to her and not to myself. So I left.

Geçmiş olsun / May it pass (to someone who is sick)

If you’ve really followed this story so far, I’m not only a little bit impressed (and in love with you) – but I’m also worried. Worried that you might think I’m a selfish bitch. Because clearly, this story wasn’t about me – but I just made it about me in like a gazillion words. See this is why I hesitated to write this down for so long. I thought: “This isn’t your story”, so it seemed wrong to make it about me. But the truth is, although I was never the victim in this story, it still affected me more than I care to admit – and it still does. I know it might sound weird, but I could never really stop thinking about Mira and everything that happened for long. In quiet hours, I found myself formulating phrases in my head, many of which I now finally found the heart to write down.

We never heard another word from Mira and she hasn’t replied to messages ever since our departure from Istanbul. That’s why I have come to accept that it’s no use for me to make this story only about her any longer. I’ve got no chance to find out how she’s coping. There’s nothing I can do to help her anymore. But there was something I thought I could do to help myself – and that was to make this story about me once and for all, hoping to finally get it to rest and out of my head.

Nobody in this story bears their real name except my lovely arkadaş Julia.

I couldn’t really understand the reason of your hate towards Turks while I was reading this article of you. I didn’t use to be able to guess you would write bad things above though you shared a photo like “Liebe ist meine religion” on instagram. I am also a Turk and I am not a part of any rape culture that you tagged in this article. As German Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said, “All generalizations are false including this one.”

I must confess that my heart was broken so much indeed when I read this article. 😥

LikeLike

First of all, thanks again for commenting, I appreciate that you took the time to read the story. It makes me a little sad to think that you would find hatred for Turkish people in the text though, because I can assure you that I do not hate Turks or any other people of this world. I have met great people in Turkey and as you could read in my other post about Istanbul, I truly loved it there. But I also had to make a very negative experience and meet some people who did not mean well, and I wrote that down. I’m sorry if I offended you as a Turk, it was by no means my intention to say that all Turks are like that, I know that they’re not. I hope you see where I’m going with this, thanks again for reaching out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I only wonder one thing. Why don’t people from the European Union love Turks? Is there a spesific reason that the peoples of the EU dislike Turks, for example, like Imperialist policies of Ottoman Empire or cultural one that is based on Eastern traditions or that most of Turkish population believe in the religion Islam? Personally, I prefer not to believe in any religion, because they are not humane and they are the reason of wars in our world. I consider Westerners and Easterners won’t be able to succeed in establishing a multicultural and supranational common Civilization as long as Westerners have an Orientalist perspective that they don’t perceive Easterners as human though both sides are human. I use the term Orientalism in a context that Edward Said wrote in his book about the subject. Despite all cultural differences between us, I am a human the same as you too. Please don’t forget this fact, dear Maria. The same as you, I feel sad as well, I fear as well, I love as well, I eat as well, I drink as well and of course, I breathe as well and my blood is red as well. In fact, for a long time, I try to understand how the peoples of the EU historically perceive Turks, but the only thing that I can find in your perception of Turks is only an enmity, despite all those colourful and cute physical appearances. For this reason, I must confess that I become more intolerant towards Westerners and I begin considering Westerners as my enemy in the context of the Latin term Hostis that German jurist Carl Schmitt wrote in his book “The Concept of the Political”, unfortunately. I wish all of us were equal in our world.

Love from İstanbul, Türkiye…

Mert

LikeLike

Interesting how you would quote that “all generalizations are wrong”, but then claim that people from Europe generally don’t like Turks. No hate towards anyone from my side, man. Have a nice day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did you even read the article? Insensitive of you to post something like this here.

Sending love to everyone involved in this. You ladies are brave.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anyway, there is no problem for me, too, Maria. I like you as well though I still have an impression like you don’t like me much. Thanks for your beautiful wishes. The same to you. 💜

LikeLike

Wow… just wow. What a horrific experience for all involved. Feeling your pain. I hope you can look back at the good experiences you had before that night with fondness, and one day get back to experience the other things you missed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Jess, thanks a lot for reaching out and taking the time to read through this mess. I appreciate your kind words and am happy to say that all the good experiences are not forgotten 🙂

LikeLike

You are not a selfish bitch. You are very brave. And so are your friends. No one can know how they will react to that kind of situation. You are probably a very empathic person and you did the best you could to help your friend and be in charge of the situation when she couldn’t. You have nothing to feel guilty about, it’s your story too and I believe it’s a good thing you talked about it. Once again, you are very brave…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so very much for that. Actually writing this down and publishing it has been incredibly hard on me, I felt like a violator of her privacy for so long when only thinking about it. But I came to realize that as you say, this story is about me, too – and it makes me feel so proud and happy to see that many people like yourself seem to agree on this and support me 🙂 Thanks for your lovely words!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for writing that. That spoke to me on another level because I went through an experience very close to this. Trust me when I say that everything you said made sense to me. No, I ABSOLUTELY do not think you are selfish. In fact, you were so much more giving than most people would have been. People say they’d do one thing and that they’re for something, but when it comes to actually coming through and taking action, they run away (like your pompous af university coordinator. Now, SHE was making the situation all about herself). You actually stuck through with her, and while I completely understand why you’d feel the need to be hesitant about talking about it, and feel like you’re intruding on her story by telling it from your point of view, I’m telling you that I don’t see you that way. I hope you’ve been able to spend some more time taking care of yourself. Self-care isn’t the easiest, but it is necessary, or else we burn out. Easier said than done, trust me, I know. Sending lots of love and hugs your way. Keep writing from the heart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am incredibly touched by all the kind words here, thank you! It feels so good to know that people who actually took the time to read the story feel that I have acted in the right way, not only in the situation but also to talk about it afterwards. All of this hasn’t been easy, but it feels so much better now that I have gotten the story off my chest and find that people support me 🙂 Thank you so very much! Lots of love to you, too!

LikeLike

I don’t see how anyone could think you’re a “selfish bitch” after reading about all you did for a girl you weren’t even sure if you liked. You’re a good person. Thank you for sharing. I know it must have not been easy to write.

Sending love xxxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Jessica, thank you for your kind words. I feel so honoured about everyone reaching out and supporting me on this, can’t thank each of you enough! Lots of love back to you xxxx

LikeLike

Oh wow, this sounds like a nightmare through and through and I would never think you’re a selfish bitch after reading this. Sure, what happened to Mira is what started it all, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t affect you profoundly as well. I’m so sorry this happened to you and I think it’s so brave how you managed to write it all down. Honestly, you sound like you were braver in these situations than I think I would have been. I might have just given up and gone home because of the stress of it. My heart goes out to you about this experience and you should feel proud at overcoming it. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Hannah, thank you for your incredibly kind comment. I really appreciate that you took the time to read my story in all it’s crazy length and reach out to me. No one ever really knows how they will cope with a situation like this, so don’t underestimate yourself – hopefully, you will never have to find out, but all of us can suddenly turn into the bravest fighters if we have to. That’s something I definitely learned from all this. Maybe you’d be surprised by all the strength that you have in yourself 🙂 Thanks very much for your words, I am literally walking on air from all of the wonderful support everyone has offered me ❤ Take care!

LikeLike

This was a strong and awful story to read. I think you have every right to make this story about you as you´ve been there all along – in fact, I really liked reading about your perspective in this (I feel “liked” is a really weird word to use in this context but can´t think of a better equivalent, sorry for that). Your classmate was very lucky to have you girls by her side to help her through all of that – I have been traveling in Turkey for some months by now and although I have mostly very positive experiences, I have encountered some disturbing sexism from some individuals and that in spite of the fact that I travel with my husband. While there is a lot of sexism in my own country too, so I don´t want to make assumptions about who is more sexist and why.

It´s really a shame they didn´t do a thing for you at the university because they absolutely should have. I hope you can overcome the trauma and feel safe again soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear GirlAstray, thanks for your lovely comment. Although you’re not fully satisfied with the word “like” in this context – be assured that I am 🙂 I truly appreciate your kind words.

It’s quiet stunning how you are still able to sense these kind of offenses with your husband around (although of course it’s great that your overall experience is a good one). I felt that when my boyfriend was visiting, the number of obvious looks I received in the street was like zero as compared to being alone. I will be reading up on your adventures in Turkey and wish you all the best for your travels there. Stay safe and enjoy 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much! Well, most of the time they don´t have particular comments when it comes to me (like twice) but when they speak about their wifes or sisters, at times it gets really disturbing. I have heard a few times that “if my sister would sleep with someone, I would kill the guy” and it is literally impossible to reason with them. Worse, these guys seem serious as it is a thing of “honor”. I am happy to say though that most men we met are totally not like this.

LikeLiked by 1 person